What’s in matcha? the complete chemical and nutritional composition

What is actually in our matcha? At Thess Matcha, we’ve gone beyond the hype to uncover the full chemical and nutritional composition of matcha — backed 100% by peer-reviewed science. From its exact caffeine content and amino acid profile to the milligrams of EGCG, vitamin C, and minerals it contains, this is the most complete, numbers-driven matcha analysis online.

Macronutrient Composition

Matcha green tea powder is notable for its high dietary fiber content and appreciable protein, with a moderate fat level. Key macronutrient values per 100 g of dry matcha include:

- Total Dietary Fiber: ~56.1 g/100 g, of which the vast majority (≈52.8 g, or 94%) is insoluble fiber and ~3.3 g (6%) is soluble fiber. This extraordinarily high fibre content means over half of matcha’s dry weight is indigestible polysaccharides. One tablespoon (~12 g) of matcha provides ~6.7 g fiber (~27% of an adult’s daily fiber recommendation). The fiber is predominantly insoluble, which has benefits for digestive health (promoting bowel function and microbial fermentation).

- Protein: ~17.3 g/100 g dry weight. Matcha is a surprisingly rich source of plant protein. Converting total nitrogen to protein (conversion factor 6.25) gives ~17% protein by weight. Thus, a tablespoon of powder (~12 g) provides ~2 g protein. The protein includes both enzymes and structural proteins as well as free amino acids unique to tea (discussed below). The overall amino acid profile of matcha protein is comparable to cereal proteins; the amino acid score (AAS) is ~40%, with isoleucine and threonine identified as the limiting amino acids.

- Total Fat: ~7.3 g/100 g. Matcha is low in fat overall (~7% by weight), but the lipids present are nutritionally notable for their unsaturation (detailed in the next section). The ash (mineral) content is around 4.6–5.3%, and the remaining fraction of matcha consists of carbohydrates (sugars, starches) and other phytochemicals. Moisture is low (~3–4%, as dry matter is ~96–97%), reflecting the powdered tea’s dried nature.

Fatty Acid Profile

Although total fat in matcha is modest, it contains a favorable fatty acid profile with a high proportion of unsaturated fats (~83.3% of matcha’s fat). The fatty acids are predominantly polyunsaturated, especially omega-3 alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). Key constituents of matcha’s lipid fraction include:

- Omega-3 (α-linolenic acid, C18:3): ~65.4% of total fatty acids. This translates to roughly 4.8 g of ALA per 100 g matcha. Omega-3 fatty acids are the most abundant unsaturates in matcha, making it an unusually omega-3-rich plant product.

- Omega-6 (linoleic acid, C18:2): ~12.6% of total fatty acids (~0.9 g/100 g).

- Omega-9 (oleic acid, C18:1): ~4.6% of fatty acids. Minor amounts of omega-7 monounsaturates are also present (e.g. palmitoleic 0.21%, vaccenic 0.50%).

- Saturated Fats: ~16.7% of total fat. The saturated fraction is almost entirely palmitic acid (~15.4% of total fat) with a small amount of stearic acid (~1.3%). This corresponds to about 1.2 g palmitic and 0.1 g stearic per 100 g matcha.

Overall, matcha’s fats are predominantly unsaturated, with omega-3 ALA being by far the largest share. In fact, among unsaturated families, omega-3 > omega-6 > omega-9 > omega-7 in abundance. Such a profile (high ALA and linoleic acid) is favorable for cardiovascular health. The total lipid in a typical serving (~2 g matcha in a cup) is very low, but the proportions highlight matcha as a source of plant omega-3. Two major saturated fatty acids (palmitic and stearic) together constitute the ~16–17% saturated portion.

Protein and Amino Acids

Matcha’s protein content (17% by weight) is complemented by a rich spectrum of amino acids, notably the unique tea amino acid L-theanine. Theanine (γ-ethylamino-L-glutamic acid) is the most abundant free amino acid in matcha, imparting the characteristic umami flavor. Dry matcha powder contains on the order of 0.3–1% theanine by weight, though this varies with tea grade and cultivation:

- Premium ceremonial-grade matcha can have nearly 1% theanine (~978 mg per 100 g in one analysis), whereas lower-grade (food grade) matcha may have ~0.35% (around 352 mg/100 g). Theanine levels decline with lower quality and later harvest leaves. This trend reflects leaf maturity: young shade-grown leaves (used in high-grade matcha) accumulate more theanine, which is remobilized from older leaves. Notably, one study found some matcha samples with exceptionally high theanine – up to 44.65 mg per g (4.465% of dry weight), illustrating that certain cultivars or production methods can yield extremely theanine-rich tea.

- Besides theanine, glutamic acid (as glutamine) and other amino acids contribute to matcha’s free amino acid pool. In ceremonial grade matcha, free glutamine was measured at ~765 mg/100 g, and other amino acids like arginine, aspartic acid, serine, threonine, alanine, valine, etc., are present in smaller quantities. For example, lysine ~102 mg/100 g and alanine ~39 mg/100 g were reported in one analysis. Theanine remains dominant, accounting for an estimated 16–69% of total free amino acids in matcha (values depending on the sample). This far exceeds theanine levels in typical non-shaded green teas, underlining matcha’s unique cultivation (shading boosts theanine retention by preventing its conversion).

- Protein quality: The bulk of matcha’s protein is in bound form (tea leaf proteins). The profile of bound amino acids shows glutamic acid, aspartic acid, leucine, lysine, arginine, and valine as the most prevalent amino acids in the protein fraction. When evaluating protein quality, matcha has an amino acid score ~40% (with wheat protein as reference ~47% AAS), indicating it is not a complete protein but comparable to other plant sources. Isoleucine and threonine are the limiting essential amino acids in matcha protein. A typical serving (e.g. 2 g in tea) provides only a small amount of protein, but when matcha is used in foods in larger quantities (~5 g daily), it contributes modestly to essential amino acid intake (e.g. up to ~8% of daily requirements for sulfur amino acids cysteine+methionine).

In summary, matcha is an excellent source of theanine, providing on the order of hundreds of milligrams per 100 g (several times higher than regular green teas), and contains a broad array of amino acids. The high free amino acid content (particularly theanine, glutamate and a small amount of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)) contributes to matcha’s umami taste and calming effects.

Vitamins, Pigments, and Minerals

Matcha supplies various micronutrients, including certain vitamins, pigments, and minerals, due to the consumption of the entire powdered leaf:

- Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid): Matcha tea is a good source of vitamin C. In fact, matcha powder contains more than double the vitamin C of ordinary green tea leaves. An analysis found 1.63–3.98 mg of vitamin C per gram of matcha powder (depending on product origin). When prepared as a beverage, a 100 mL cup of matcha can provide on the order of 39–70 mg of vitamin C (this corresponds to ~390–700 mg/L in various matcha infusions). For comparison, Jakubczyk et al. observed ~32–45 mg/L vitamin C in matcha brewed at different temperatures. These values indicate matcha infusions can supply a significant amount of vitamin C, approaching the content of lemon juice or orange juice per serving.

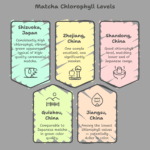

- Fat-Soluble Vitamins and Pigments: Green tea leaves naturally contain antioxidant vitamins like tocopherols (vitamin E) and precursor pigments like β-carotene (provitamin A). While specific quantitative data for carotenoids in the provided documents is limited, it is noted that green tea (including matcha) contains carotenoids and tocopherols alongside its polyphenols. Chlorophyll content, however, has been quantified: matcha’s shade-grown leaves have a very high chlorophyll level, which gives the powder its vibrant green color. Tencha leaves (used for matcha) were found to contain ~5.65 mg of chlorophyll per gram dry weight, versus ~4.33 mg/g in non-shaded green tea leaves. This ~30% higher chlorophyll content is a direct result of shading (the plant compensates for low light by producing more chlorophyll). Matcha’s bright hue and potent antioxidant activity are partly due to these chlorophylls and their derivatives. (In stored matcha some chlorophyll may convert to pheophytins; indeed, NMR analysis detected chlorophyll derivatives like pyropheophorbide and pheophytin in matcha.) The carotenoid content (e.g. lutein, β-carotene) is not explicitly measured in these sources, but given that tea leaves contain carotene and xanthophyll pigments, matcha likely provides a few milligrams per 100 g of total carotenoids (contributing to its color and antioxidant profile).

- Minerals: As a whole-leaf product, matcha is relatively rich in certain minerals. It provides notable amounts of potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), manganese (Mn), iron (Fe), calcium (Ca), zinc (Zn), and trace elements, though the levels reflect soil and cultivation differences. Among these, potassium is the most abundant mineral in matcha. Reported K concentrations are around 9.4–9.7 mg/g (0.94% of dry mass), significantly higher than any other element. For example, one study found K ~9.38–9.71 mg/g and Mg ~2.68 mg/g, with Mg being the second-highest mineral and Mn the third (Mn ~1.16–1.55 mg/g in the same samples). In other words, 100 g of matcha contains on the order of 0.94 g K and 0.2–0.3 g Mg. Manganese is also present at high levels (~1.5 mg/g) and matcha can contribute substantially to manganese intake. Indeed, a 5 g serving of matcha could provide ~7.5 mg Mn, which is ~15–19% of the Adequate Intake (AI) for an adult (male or female). Iron and zinc are present in smaller but notable amounts: in one analysis Fe ranged from ~70 to 220 µg/g and Zn ~30 to 40 µg/g in different matcha brands. This means ~0.07–0.22 mg Fe and ~0.03–0.04 mg Zn per gram of matcha. While matcha is not a major source of iron or zinc in absolute terms, a typical serving (2 g) could provide a few percent of daily Fe/Zn needs. Calcium in matcha was on the order of 0.6–0.8 mg/g (i.e. ~60–80 mg per 100 g). Sodium is very low in matcha (around 20–30 µg/g), reflecting tea’s nature as an unsalted plant product. Importantly, some trace minerals in matcha like selenium (Se) and chromium (Cr) are present only at trace levels; matcha is not a significant source of Se or Cr for human nutrition. For instance, total Se in matcha was about 3.3 µg/g in one study, and much of that remains in the insoluble fraction after digestion (limited bioavailability).

Mineral bioaccessibility is a consideration since matcha is consumed as a suspension of fine particles. Research using in vitro digestion showed that not all minerals leach into solution; e.g. only ~18–37% of Na, Fe, and Se were released into a cold water “ice tea” infusion in one experiment. However, because one ingests the whole powder, minerals not initially dissolved can still be absorbed during gastrointestinal transit. Overall, matcha can modestly contribute to the RDA of various minerals; for example, a few grams of matcha can provide ~5–7% of daily iron and zinc (for females), and as noted above close to 15–20% of manganese requirements. It is also a source of trace copper (Cu) and others (matcha Cu and Mn were the top contributors toward recommended intakes among trace metals). Toxic heavy metals (lead, cadmium, mercury) in matcha were below safety limits in tested samples, so consumption in typical amounts is regarded as safe.

In summary, matcha’s micronutrient profile features high vitamin C, significant chlorophyll and related pigments, and a mineral spectrum dominated by K, Mg, and Mn (with smaller amounts of Ca, Fe, Zn, etc.). These compounds add to matcha’s health value: for instance, chlorophylls and carotenoids act as antioxidants, and trace elements like Mn function as enzyme cofactors.

Polyphenols and Antioxidant Compounds

One of matcha’s most celebrated aspects is its abundance of polyphenolic compounds. Because matcha consists of whole ground tea leaves (rather than an aqueous extract like brewed leaf tea), it delivers very high levels of flavanols, phenolic acids, and flavonols. Polyphenols contribute to matcha’s potent antioxidant capacity and health benefits. Key constituents and quantitative findings include:

- Total Polyphenols: Matcha is extremely rich in polyphenols. A study by Koláčková et al. measured the total polyphenol content of matcha powder (via Folin-Ciocalteu assay) as 169–273 mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram. This means polyphenols constitute roughly 17–27% of matcha’s dry weight as phenolic equivalents. By comparison, conventional green teas brewed in water show much lower yield per gram of leaves. Indeed, brewed matcha infusions (which use the whole powder) also exhibit high phenolic concentrations: in various matcha samples, total phenolics ranged ~820 to 1018 mg GAE per liter of prepared tea. For flavonoids specifically, one study found 864.7–1034.4 mg rutin equivalents per liter of matcha tea. These values are markedly higher than typical brewed green tea, owing to the fact that matcha drinkers consume the suspended leaf particles and extract a greater fraction of compounds.

- Catechins (Flavan-3-ols): Green tea catechins are the signature polyphenols in Camellia sinensis, and matcha is considered the most concentrated source of catechins. There are four major catechins in green tea – (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), (−)-epigallocatechin (EGC), (−)-epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG), and (−)-epicatechin (EC) – with EGCG being the most biologically potent and abundant. Quantitatively, matcha powder contains on the order of 5–6% by weight total catechins. NMR analysis of matcha found total catechins ~5–6 g per 100 g. Specifically, EGCG was about 2.0–2.7 g/100 g (i.e. ~2% to 2.7% of dry mass), EGC around 1.2–2.5 g/100 g, ECG around 0.5–0.9 g/100 g, and EC roughly 0.2–0.3 g/100 g. For example, in one ceremonial-grade matcha, EGCG was measured at 2665 mg per 100 g and EGC at 1197 mg/100 g. Lower-grade matcha showed slightly lower EGCG but higher EGC (consistent with studies noting young, shade-grown leaves have relatively less EC/EGC). Importantly, even the lower end of these ranges is very high compared to other foods – a 2 g serving of matcha likely provides on the order of 40–50 mg of EGCG, far surpassing the EGCG in a typical cup of brewed green tea. These catechins are responsible for many of matcha’s antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. In fact, EGCG is considered the principal active compound in green tea, and matcha delivers it in high doses. Studies confirm matcha’s catechin content is significantly greater than that of leaf green teas; one report found green tea infusions had 5.5–7.4 mg/g catechins vs. matcha with 18.9–44.4 mg/g. Matcha’s catechins have an inverse relationship with quality grade: premium grade (G1) teas, due to heavy shading and use of younger leaves, tend to have slightly lower total catechins (but more theanine), whereas food grades (older leaves) have higher catechin concentrations. Nevertheless, all grades of matcha are catechin-rich. Notably, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) is one of the most abundant single compounds in matcha; in a top-grade sample ~2.66% was EGCG. Epigallocatechin (EGC) was even higher in some lower-grade powders (~2.5%), whereas epicatechin gallate (ECG) and epicatechin (EC) are present at lower levels (sub-percent range). HPTLC fingerprints show all these catechins are present in matcha and increase in content from grade 1 to food grade. In summary, matcha provides a high dose of catechins (totaling several grams per 100 g powder), underpinning its strong antioxidant capacity.

- Flavonols and Other Polyphenols: Beyond catechins, matcha contains a variety of flavonol glycosides and phenolic acids. Rutin (quercetin-3-rutinoside) is one flavonol present in especially high concentration. Jakubczyk et al. reported that a matcha infusion contained 1968.8 mg/L of rutin – a striking amount, considering buckwheat (one of the richest rutin foods) has about 62 mg/100 g. This suggests a cup of matcha can provide tens of milligrams of rutin, a bioflavonoid known for strengthening blood vessels and synergizing with vitamin C. Kika et al. directly measured rutin in matcha powder by HPLC and found about 35.3 µg/g (which is 0.035 mg/g). This dry weight figure may appear modest, but when the powder is consumed as tea, the effective concentration in the beverage becomes significant (as reflected in the high mg/L infusion levels). Other flavonols identified in matcha include myricetin, quercetin, kaempferol, and apigenin (a flavone). Kika et al. found myricetin at 108.2 µg/g, quercetin at 5.3 µg/g, kaempferol at 1.46 µg/g, and apigenin at 8.3 µg/g in matcha powder. Although these values are in the tens of µg per gram (ppm range), they indicate the presence of a broad spectrum of antioxidant flavonoids. It’s worth noting that when matcha is prepared, quercetin can be extracted in higher amounts – e.g. one study measured ~1.2 mg/mL quercetin in a matcha extract (slightly higher than in a comparable green tea), and Koláčková et al. reported up to ~17.2 µg/g quercetin in matcha powder using an alcoholic extraction. Thus, matcha provides small but appreciable quantities of these health-promoting flavonols.

- Phenolic Acids: Matcha contains numerous phenolic acids (many of them are breakdown products or intermediates of polyphenol metabolism in the plant). HPLC analysis (Jakubczyk et al.) of matcha powder found gallic acid to be the most abundant phenolic acid, at 252.4 µg/g. Other phenolic acids detected (in descending order of amount) included 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (~41.8 µg/g), sinapic acid (~29.2 µg/g), ferulic acid (~15.5 µg/g), ellagic acid (~10.8 µg/g), and p-coumaric acid (~3.3 µg/g). Notably caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, and protocatechuic acid were below detection in that particular analysis. However, other studies have shown matcha can have considerable amounts of some of these compounds. Koláčková et al. reported, for instance, chlorogenic acid up to 4800 µg/g (0.48%) in certain matcha samples – though this value is exceptionally high and might refer to a specific extract or a unique sample. The same study found gallic acid up to 423 µg/g and p-hydroxybenzoic acid ~243 µg/g, indicating variability by origin. In the 2025 NMR metabolomics study, chlorogenic acids and related compounds were also detected; interestingly, they observed higher total chlorogenic acids in lower-grade matcha (food grade) than in ceremonial grade. They quantified “total chlorogenic acids” in food-grade matcha at ~230 mg/100 g vs ~115 mg/100 g in grade 1, and identified shikimic acid (a precursor in phenolic biosynthesis) accumulating more in high-grade leaves. Overall, matcha provides a wide array of phenolic acids, mostly at sub-milligram-per-gram levels, which collectively contribute to its antioxidant potency.

- Other Polyphenols: A unique polyphenol noted in matcha is resveratrol (more commonly associated with grapes); Kika et al. detected resveratrol at 14.48 µg/g in matcha. While this is a very small amount, its presence exemplifies the diverse phytochemicals in matcha. Additionally, NMR analysis found caffeoylquinic acid derivatives and other minor polyphenols in matcha. The total antioxidant capacity of matcha infusions is correspondingly high – for example, Trolox-equivalent antioxidant capacity of various matcha teas ranged ~7.3–9.5 mM in one study, and FRAP (ferric reducing power) values ~1845–2266 µM Fe(II)/L, which are significantly higher than many common vegetables or beverages on a per volume basis.

In summary, matcha’s polyphenol profile is characterized by high levels of catechins (notably EGCG), abundant flavonol glycosides like rutin, and a variety of phenolic acids and minor polyphenols. The quantitative data underscore matcha’s potency: on a dry weight basis, upwards of 5–6% is catechins, and total polyphenols may approach 20% or more. This dense concentration of antioxidants is what gives matcha its reputed health benefits and a strong antioxidant ORAC/FRAP activity. Many of these compounds (EGCG, quercetin, rutin, etc.) have been linked to anti-cancer, cardioprotective, and neuroprotective effects in the scientific literature.

Caffeine and Other Phytochemicals

Caffeine is another prominent component of matcha. Due to the shading of tea leaves and use of younger buds, matcha accumulates more caffeine than many other green teas. On a dry weight basis, matcha powder typically contains around 2–4% caffeine. Kika et al. measured 2213.5 µg/g of caffeine in matcha, which is approximately 2.21 mg per g (0.22% by weight). However, other studies have reported higher values: for instance, Koláčková et al. found matcha powders in the range 18.9 to 44.4 mg of caffeine per g, i.e. up to ~4.4% caffeine. This range was higher than that observed in other green teas (which had ~11.3–24.7 mg/g). The variability depends on leaf age, cultivar, and processing, but clearly matcha is among the most caffeinated forms of green tea. In practical terms, a 2 g serving of matcha could provide anywhere from ~40 mg to over 80 mg of caffeine (the latter if one assumes ~4% content), comparable to or exceeding a cup of brewed coffee in some cases. In the study by Jakubczyk et al. on different matcha products, infusions ranged from 823.3 to 7313.2 mg of caffeine per liter. Even the lower end (~823 mg/L) is equivalent to ~82 mg per 100 mL cup, and the highest value (~7313 mg/L) is extraordinarily high (this might reflect a very concentrated preparation or an assay of suspended solids). Most commonly, a serving of matcha tea (~100–150 mL) provides on the order of 70–100 mg caffeine. Experimental data confirm matcha’s caffeine content is significantly greater when consuming the powdered form versus brewing leaves – Fujioka et al. found powdered tea yielded more caffeine in the cup than leaf infusions, especially at higher temperatures.

Importantly, other xanthine alkaloids found in tea (such as theobromine and theophylline) are present only in trace amounts in matcha. Analytical tests in one study did not detect theobromine or theophylline in matcha samples, likely because their concentrations are very low (orders of magnitude lower than caffeine) or they were not effectively extracted. Green tea generally contains only minor levels of these compounds compared to caffeine, and matcha is no exception. Thus, caffeine is by far the dominant stimulant in matcha, whereas theobromine/theophylline contribute negligibly (if at all) to its effects.

L-Theanine, discussed earlier, also deserves mention here as it works in tandem with caffeine. While not a xanthine, theanine is a psychoactive compound that can modulate caffeine’s effect by promoting relaxation without drowsiness. Matcha’s caffeine-to-theanine ratio is considered ideal for providing sustained energy and focus. For example, a typical matcha serving might contain ~70 mg caffeine and 20–30 mg theanine (depending on quality), a combination shown to improve alertness and cognitive function synergistically. In high-grade matcha, theanine levels are particularly high, which contributes to the smooth, less-bitter stimulant effect of matcha as compared to coffee.

Beyond polyphenols and caffeine, other phytochemicals in matcha include saponins, chlorophylls, and organic acids that can have functional effects. Tea saponins (triterpenoids) are present in small quantities and may contribute to matcha’s emulsifying properties (relevant for the famed matcha “foam” when whisked). Matcha’s chlorophyll content has already been noted – chlorophyll itself has been studied for potential detoxification and anti-inflammatory properties. The organic acids in matcha (such as quinic acid, malic acid, and others) can influence flavor and antioxidant activity. NMR analysis found significant amounts of quinic acid (e.g. ~0.59% in grade 1 matcha) and shikimic acid, which relate to polyphenol biosynthesis and taste.

Finally, matcha contains pigments and degradation products such as pheophytins (from chlorophyll) and possibly Maillard reaction products from drying, although high-quality matcha is processed gently to avoid oxidation. Trace volatile compounds (e.g. linalool, geraniol) give matcha its aroma but are present in minute quantities.

In conclusion, matcha green tea is a chemically complex, nutrient-dense powder. It provides macronutrients like protein (17% wt) and fiber (56% wt) in significant amounts for a leaf product, alongside essential fatty acids (with a notable omega-3 ALA content). It is packed with amino acids (especially theanine ~1%) and has a robust profile of micronutrients (vitamin C, vitamin E, β-carotene, and minerals like K, Mg, Mn). The polyphenol load is exceptionally high – matcha delivers catechins (EGCG and others) on the order of grams per 100 g, plus diverse flavonoids (rutin, quercetin) and phenolic acids (gallic, etc.) in measurable amounts. Caffeine content is also high, on the order of 2–4% (dry weight), contributing to matcha’s stimulating properties, balanced by the calming theanine. All these constituents work in concert, making matcha a unique functional food with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and stimulant effects. Every cup of matcha can be seen as a concentrated shot of tea’s nutritional and phytochemical wealth, which is why it has been lauded for its health benefits in both traditional usage and modern research.

About Thess Matcha

At Thess Matcha, every batch starts with precision and ends with excellence. Our work goes beyond sourcing — we invest in research & development, apply strict quality control, and drive innovative product development so every scoop delivers purity, potency, and incredible flavor.

From the vibrant green color to the rich umami taste, everything we do is designed to make your matcha experience unforgettable.

Follow us on Instagram @thessmatcha for behind-the-scenes R&D, new product drops, and matcha inspiration.

Sources: Jakubczyk et al., Foods 2020; Kika et al., Foods 2024; Kolačková et al., J. Food Comp. Anal. 2020; Kochman et al., Molecules 2021; Toniolo et al., Plants 2025; Jakubczyk et al., Foods 2024 (1270); Kika et al., Foods 2024 (1167).